James Ensor

Born

1860-04-13Deceased

1949-11-19Collection

Musea Brugge , Mu.ZEE, Art Museum by the Sea , Museum of Fine Arts Ghent , Royal Museum of Fine Arts AntwerpPeriod

19th century , 20th centuryMore about James Ensor

James Sidney Ensor (Ostend, 13 April 1860-19 November 1949) was the son of an English father (James Frederic) and a Belgian mother (Maria Catharina Haegheman). With an eye on obtaining the title of baron, only in 1929 did Ensor seek naturalisation. Up until that point he retained his father‘s nationality. The family operated a souvenir and curiosity shop in Ostend and boarded rooms out to summer guests. The young Ensor attended the College of the Blessed Virgin in Ostend.

1876-1880: Education

In 1876, Ensor attended drawing lessons at the local drawing school. During the spring and summer months he painted dozens of small nature studies on pink cardboard. From 1877 until 1880 he studied at the academy in Brussels. He received lessons from the Director, Jean Portales, among others. Fernard Khnopff, Theo Van Rysselberghe, Willy Finch and other future members of the exhibition associations, L'Essor and Les Vingt, were among his fellow students. In Brussels, he met the poet and art critic Théo Hannon, who introduced him to the liberal circles of Ernest Rousseau, professor at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, and his younger spouse, the nature expert Mariette Rousseau Hannon. The home of the Rousseau couple was a meeting place for the artistic, literary and scientific elite of the time. The contacts that Ensor had there-where he probably met Félicien Rops and Eugène Demolder and others-stimulated his artistic and intellectual development. Around the time of 1886-1889, Ensor would rework a number of his academic pieces into grotesque productions.

1880-84: debut

In 1880 Ensor installed a studio in the attic of his parents‘ home in Ostend where he would work every now and then in the company of Willy Finch. Although he lived in Ostend until his death, he regularly stayed in Brussels and actively participated in the artistic life of the capital city. With the exception of a few excursions to London, Holland and Paris, Ensor scarcely traveled.

In 1881, he debuted with the progressive Brussels art circle, La Chrysalide. He qucikly became recognised by friend and enemy alike as one of the prominent artists of the time. His seascapes, still lifes, naturalistic figure pieces and tableaux from the life of the young, modern bourgeois woman, such as the celebrated The Oyster-eater from 1882, unquestionably belong to the major works of the European Realism and plein aire movements.

In 1883 Ensor, along with a few older students of the Brussels‘ academy, would take leave of the artists‘ association L'Essor. They established the artists‘ association Les Vingt. This will play an important role in the dissemination of various international avant-garde movements.

1885-90: experiment

Between 1885 and 1888, Ensor‘s attention went chiefly to drawing and etching. Under the influence of Rembrandt, Redon, Goya, Japanese woodcuts, Brueghelian images and contemporary spoofs, Ensor developed a highly personal iconography and design. He rejected French Impressionism and Symbolism and lent himself to the expressive qualities of light, line, colour and the grotesque and macabre motifs such as carnival masks and skeletons, which he rendered in massive tableaux such as in the series The Aureoles of Christ or The Sensibilities of Light (1885-1886). These grotesque metamorphoses culminate in Ensor‘s most well-known and monumental mask tableau: The Entry of Christ into Brussels (1888-1889, oil on canvas, Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum).

The women in Ensor's life

Around 1888 Ensor would meet Augusta Bogaerts with whom he maintained a lifelong relationship, though without ever living together with her. After the death of his father in 1887, Ensor was often charged with the care for his mother, his live-in aunt Mimi, his divorcée sister Mariette (or Mitche) and her daughter Alexandrine, as well as the management of the family store, the most important source of income.

Early Successes

In 1893 Ensor fruitlessly set himself against the dissolution of the art circle Les Vingt. Octave Maus, secretary of Les Vingt, founded the exhibition association La Libre Esthétique. Ensor was regularly courted by La Libre Esthétique. The Print Room of the Royal Library in Brussels purchased a large number of etchings in 1893, followed one year later by the Kupferstichkabinett Museum of Prints and Drawings in Dresden and in 1899 by Albertina of Vienna. The rumour that in 1893 Ensor had offered unsuccessfully to sell the complete contents of his studio for 8.500 Belgian Francs (BEF) has never been documented and appears unlikely in light of his growing commercial success. In 1895, Ensor successfully solicited the Minister of Internal Affaires for the purchase of The Lamps (1880, oil on canvas) for the National Museum (the present-day Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels). Ensor asked 2.500 BEF for the work. In 1897, he again successfully asked the city government of Ostend to purchase a painting for the City Museum. Ostend paid 2.000 BEF for Sick Wretch Warming Himself (1882, oil on canvas, destroyed in 1940). Ensor participated more actively in the local artistic life in Ostend and became chair of the Cercle des Beaux-Arts, which he established.

Ensor‘s artistic rejuvenation was noticed by German artists and critics around 1900. Alfred Kubin, Paul Klee, Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Georg Grosz, Herbert von Garvens-Garvensburg or Wilhem Fraenger understood that 'le peintre des masks‘ (the painting of masks) radically broke with the classical West-European artistic values and traditions.

He was also recognised in Belgium as one of the pioneers of Modern Art. François Franck and the admirers who were members of the Antwerp exhibition association L'Art contemporain would successfully promote Ensor‘s work, both at home and abroad.

Beginning in 1896, Ensor already was promoting himself more as a writer. Franz Hellens, who in 1974 wrote the foreward in one of the editions of Ecrits, spoke about 'maddest words‘ and indicated that this 'is the real Ensor [...] the sword-wielding and honeyed Ensor, biting and irreverent, naïve and cynical. The greatest enfant terrible that painting has ever known, a child in all the genuine and terrible connotations of the word‘. Primarily Ensor published on art in the newspapers Le Coq Rouge and La Ligue artistique. Later he was asked more and more as an occasional speaker and he took advantage of this opportunity to bring attention to the division of the sand dunes, modern architecture and vivisection.

The Musician

In a number of speeches Ensor called himself a forerunner of Luminism, Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism, Futurism and Surrealism. Ensor also placed especially great importance on his musical productions. In 1911, he wrote the libretto and composed the music for a ballet entitled La Gamme d'amour. For this pantomime he also developed the décor and costumes. In 1924, this ballet was performed in the Antwerp opera house. In 1917, Ensor moved to the house in the Vlaanderenstraat/Rue de Flandre that he had inherited from his uncle. Today, the James Ensor museum is housed here.

(Text: Herwig Todts, with contributions by Cathérine Verleysen and Robert Hoozee)

Ensor as Painter

There are approximately 850 paintings known to be by the hand of James Ensor. From 1876 until 1883 and from 1889 until 1892, he was especially productive. After 1920 he worked with a renewed enthusiasm for 20 years. Between 1873 and 1941 not a year passed without him producing at least one painting.

From 1881 until his death, Ensor participated in exhibitions in which he presented his work to colleagues, critics and discerning admirers. Ensor sold little or nothing for twenty years. After 1900, he sold the greater part of his oeuvre to collectors who belonged to the public of the Antwerp exhibition association L’Art contemporain and the Brussels‘ Galerie Giroux.

In technical, iconographical and stylistic respects, Ensor‘s painting oeuvre is extraordinarily diverse. He places great importance, in opposition to what was at one time asserted, on the quality of the materials used and gladly tries out various types of equipment, materials and techniques.

Before 1887, Ensor often painted very informal, refined realistic studies, seascapes, landscapes, still lifes and modern-genre tableaux. Among these a few undisputed masterpieces are found such as Russian Music (1881), The Oyster-eater (1882) or the Portrait of Willy Finch (1882). In 1887, Ensor chose for a grotesque or satirical depiction of motifs for which he sought inspiration in the Bible, literature, history, contemporary social and artistic life, his personal life, the world of the carnival, commedia dell’arte and ballet. He does this in a contrast-rich and vivid colouration, at times in an expressive design, then at others in a naïve form. He paints but a handful of important landscapes. However, throughout his life Ensor painted a great number of still lifes. Through the introduction of masks, but also by means of a combination of trivial objects, these still lifes obtain a double entendre character.

(Text: Herwig Todts)

Ensor as Draftsman

Few artists have attributed such meaning to drawing as James Ensor. Painting and drawing are on the same level for him. Among other things, this seems to be apparent from the fact that Ensor also entered drawings for exhibitions as legitimate works of art. Some of his drawings are executed on a large format so that they could further compete with the paintings.

As a young artist, Ensor usually used gaphite or black chalk to render his direct surroundings as image. He filled sketchbooks with portraits and fragments of his interior. Drawings after nature are rather rare.

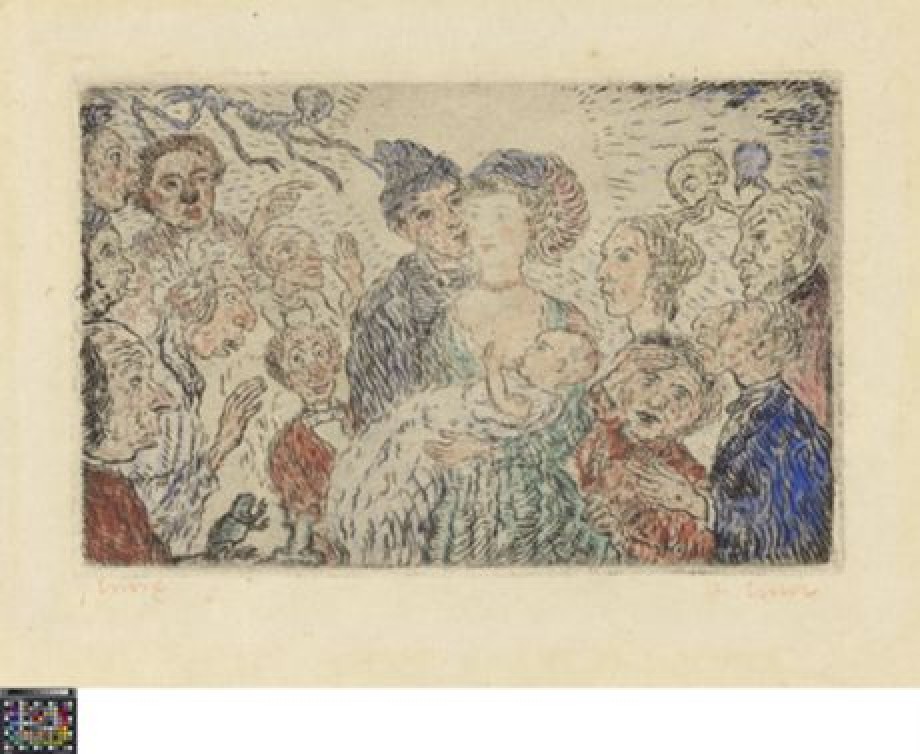

During the years 1885-1887, when his art took a new turn and the fantastic and satirical entered the picture, it appears that even then the artist gave preference to drawing over painting. He created the great The Aureoles of Christ or The Sensibilities of Light (1885-1886) in which he depicted a mass of figures under a supernatural light. The Aureoles of Christ consists of six drawings. Two works are in the Museum of Fine Arts Ghent and two are preserved in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels. The other drawings are in private possession (in Belgium and the United Kingdom).

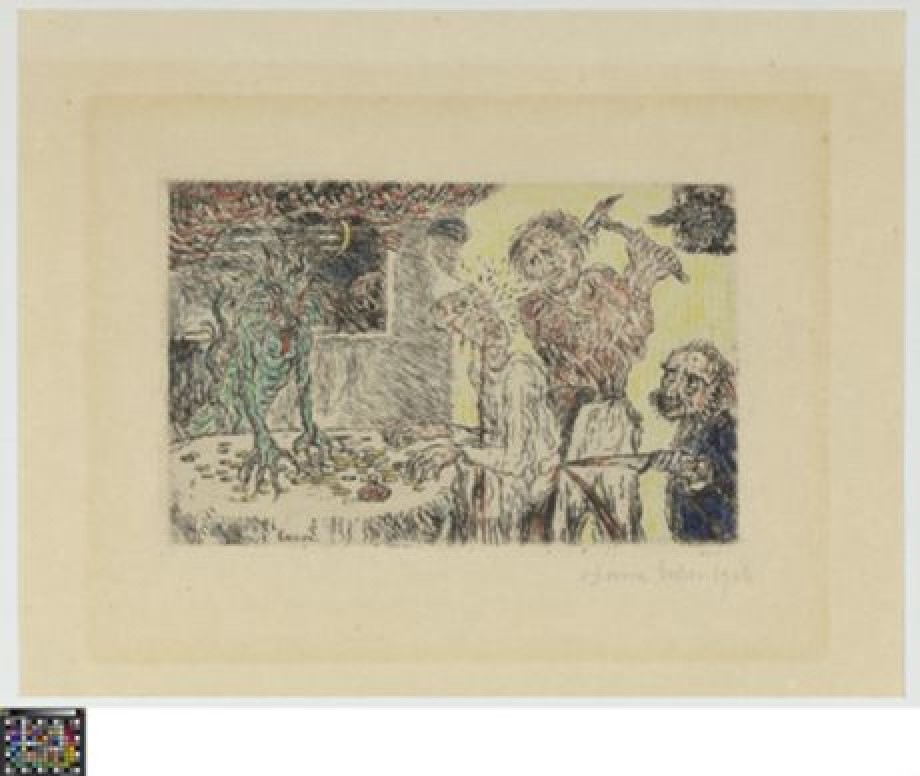

In addition, Ensor drew various motifs, which he grouped under the titles ̳fantasies and grotesques‘. During this period, Ensor also had the peculiar habit of drawing over older, realistic sketches in order to transform them into surreal compositions. The coda of this drawing adventure is a curious collage of 71 drawings assembled together in a bizarre representation of The Temptation of St. Anthony (1887, mixed technique, Chicago, The Art Institute).

In his small and large drawings from the period 1885-1890, Ensor developed a personal style to suggest light effects with shading and a fine pattern of lines. As seen from the line pattern, the typical arabesques and graphic fantasies are already present on paper, that we also encounter in Ensor‘s paintings from ca. 1887 onwards. After 1890, the drawing is less prevalent in Ensor‘s oeuvre. The later drawings are often executed in colour, by which they sometimes resemble small paintings. Worth noting is that Ensor‘s oil paintings from the same period also take on a more graphic character for their part.

(Text: Robert Hoozee)

Ensor as Graphic Artist

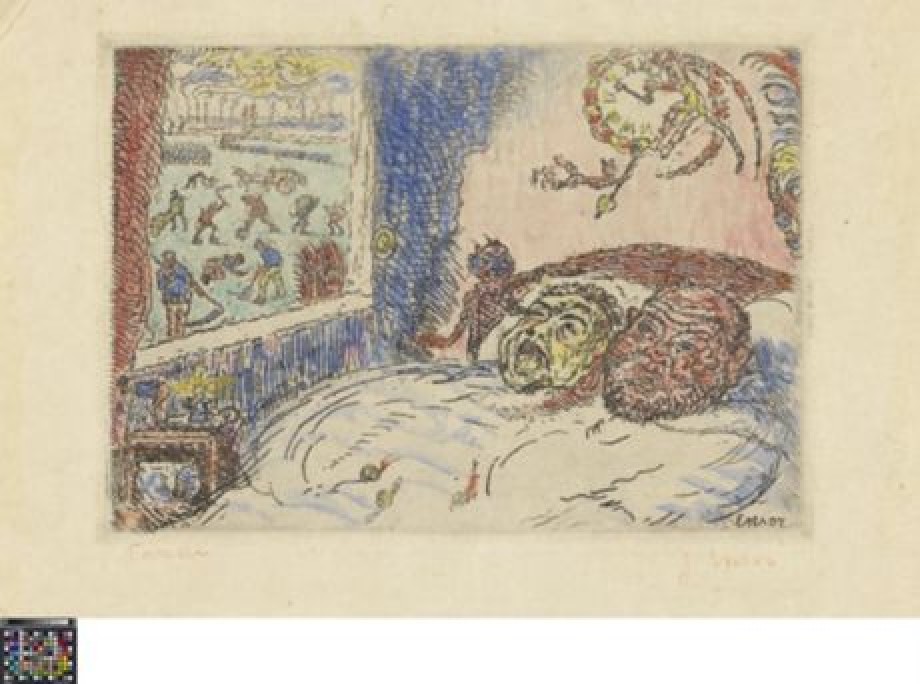

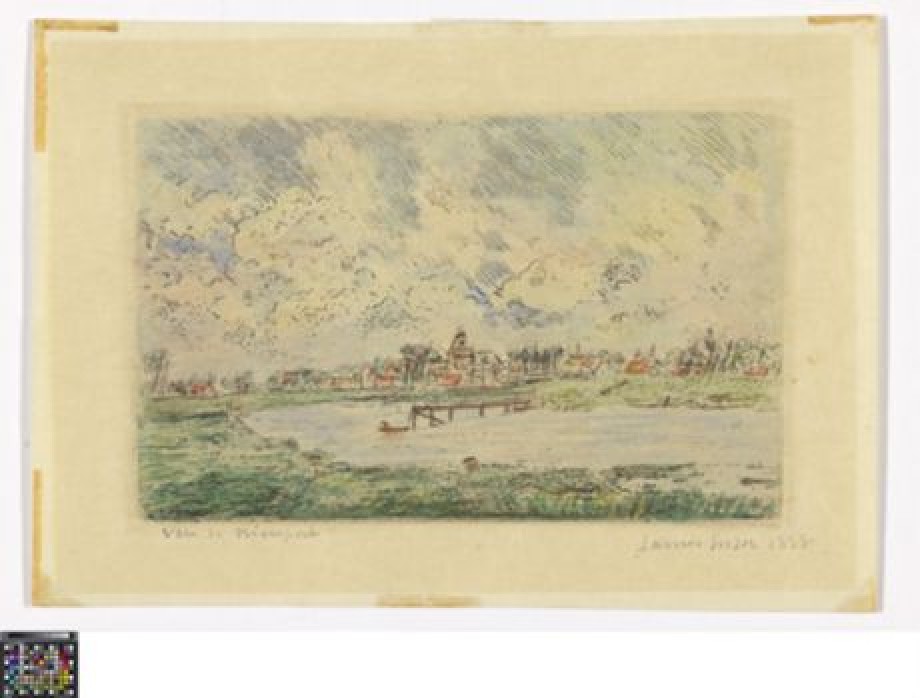

The study of light was one of the central subjects in the artistic debate at the end of the 19th Century. James Ensor also obsessively analysed light and dark. These studies led to the realisation of his first sketches. Light and caricature are the two poles between which he continuously moved with his sketches.

In his landscapes and cityscapes he concentrated on a correct representation of the atmosphere. By contrast, in a number of other compositions he allowed fantasy and social critique to take centre stage.

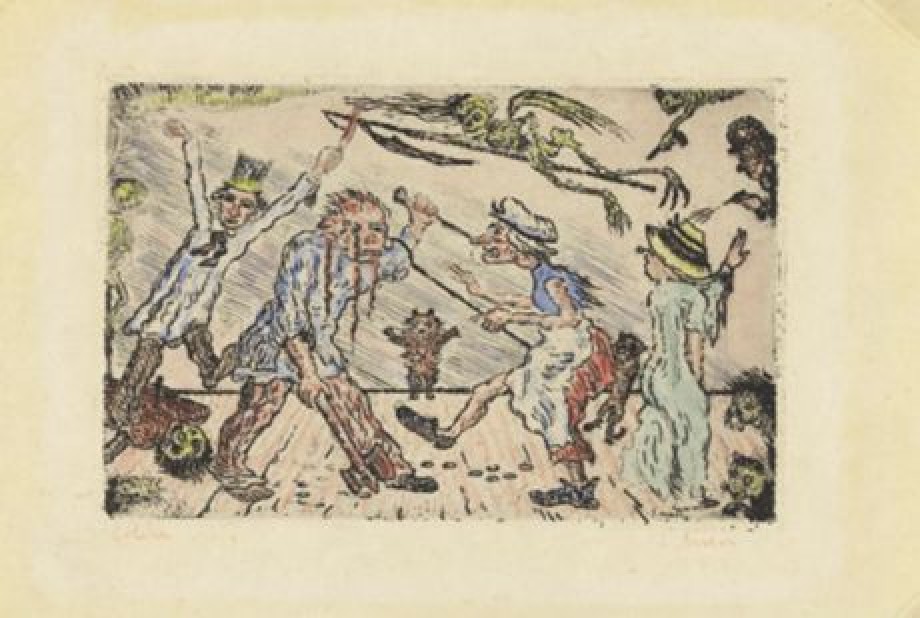

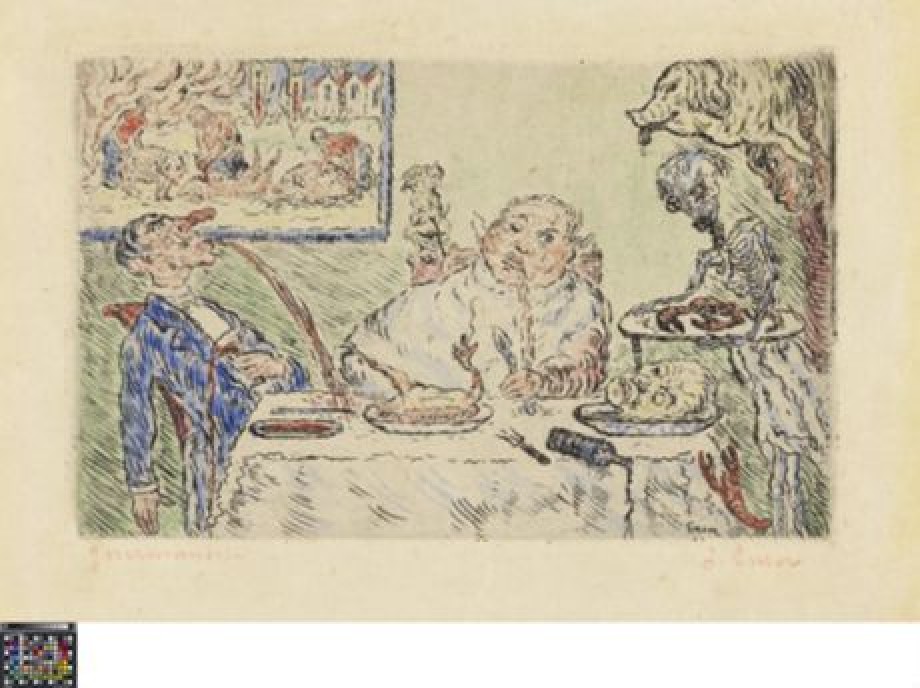

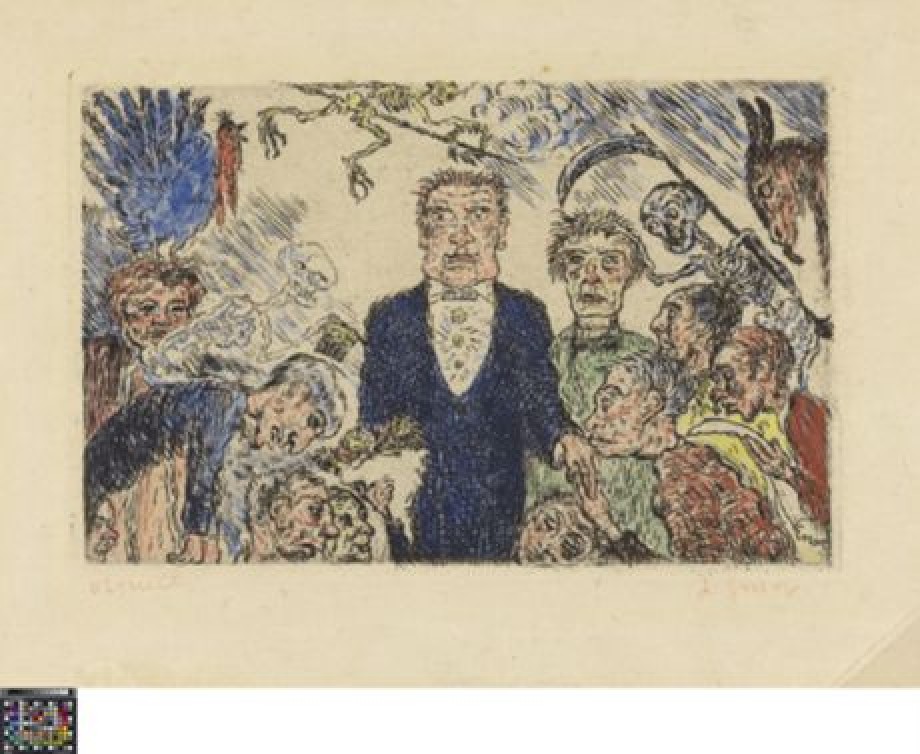

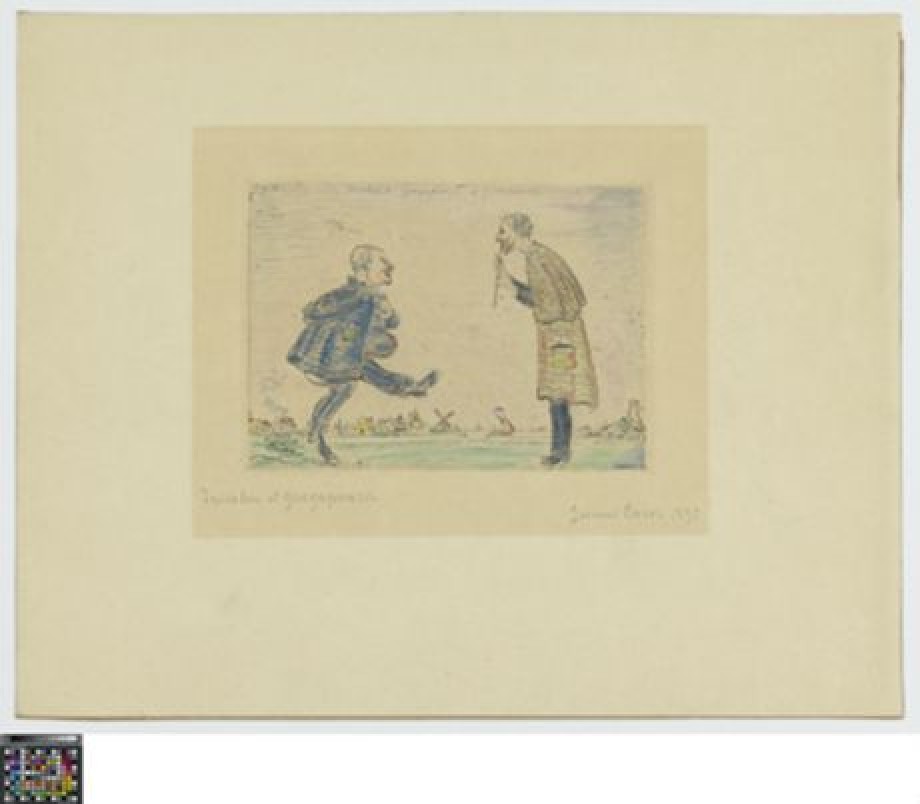

Fueled by the analysis of the Great Masters and reading classical authors, Ensor created his rich imagination. Among others, The Infernal Cortege (1887) and Devils Thrashing Angels and Archangels (1888), are the prints that surprise by means of their caricature nature and through the explosive handling of the subject. Meanwhile, the political debates and social changes of his time did not leave Ensor unfased. With Belgium in the 19th Century (1889, copper etching, Ghent, Museum of Fine Arts) and Doctrinal Nourishment (1889, zinc etching, Ghent, Museum of Fine Arts) he did not hesitate to take a standpoint against the established order. Ensor produced the majority of his gravures, 88 of the 133, in a very brief period, from 1886 to 1891. He did this with the dry-point etching technique. The creative explosion of Ensor‘s engraving art that dominated until 1891 gradually ended. Afterwards, the print became merely a manner to give more notoriety to his other creations through the means of the multiplicity of the etching.

(Text: Sabine Taevernier)

James Ensor as Musician

Blanche Rousseau, Maurice des Ombiaux, Paul Haesaerts, Karel Jonckheere, Emma Lambotte and others have described how Ensor could entertain company in a comic manner by playing a pennywhistle in one of his nostrils, and with imposing, hilarious and fearsome improvisations played out on the piano.

Ensor was musically active already in the 1880's. The oldest composition of his that is preserved is the waltz Enlacements, dated 1905. Pietro Lanciani, who directed concerts in Ostend with Ensor's favourite dance and amusement music, revised a few of Ensor's pieces for symphonic orchestra and before the first World War had already given a few performances.

In 1906, the collectors Albin and Emma Lambotte presented the artist with a harmonium. Ensor composed various musical pieces that he collated into a six-part work for ballet, which he completed in 1911. La Gamme d'Amour consists out of the following parts: (1) Flirt des marionettes (1907), (2) Lento and Andante or Complainte et Berceuse, (3) Gamme d'amour (false), (4) Marche funèbre, (5) Enlacements (1905), (6) Pour une orgue de Barbarie (1911).

In these years, Ensor would from time to time attend concerts as the performer of his own piano pieces. He could not score his own compositions- as he played by memory-, and he played in an unorthodox way, with outstretched fingers, primarily the black keys of the keyboard. His music was scored and revised for symphonic orchestra by other musicians such as Michel Brusselmans and Georges Vriamont.

Ensor took his musical work very seriously. Without success, he undertook a few attempts to have the ballet La Gamme d'amour performed in the Théâtre des Champs Elysées or by La compagnie des Ballets russes, both in Paris. He complained about Brusselmans's orchestration of his composition that it would weaken its progressive character. Ensor related repeatedly that some musicians had at times compared his musical inventiveness with Claude Debussy (1862-1918). The prominent Belgian organ virtuoso, professor at the Antwerp conservatory, Brussels and Mechelen and international acclaimed composer, Auguste De Boeck, can but bring a mild praise for what he calls Ensor's simple dance tunes.

La Gamme d'amour was played for the first time by a student group of the Ostend music academy in 1917 and was consequently directed by Léon Delcroix in the exhibition hall in Brussels where George Giroux in 1920 organised a restrospective of Ensor's plastic work. François Franck financed the first full performance of the ballet for which Ensor also had indeed designed a staging, costumes and decor. With the choreography of Sonia Korty and under the direction of Flor Bosmans, Poppenliefde premiered on 27 March 1924 in the Royal Flemish Opera in Antwerp. In 1927, François Gaillard directed a few performances in the Théâtre Royal in Liège. There also exist sung variations and versions for fanfare, carillon and harp.

For the occasion of the grand retrospective in 1929 in the Brussels Palace of Fine Arts, Georges Vriamont secured the publication of an album with the staging, the score for piano and lithographs with the most important personages from the ballet. Furthermore, still two more compositions from the 1920's are known.

(Text: Herwig Todts)

James Ensor as Writer

Ensor was criticized on occasion as "the benighted and supremely naïve artist" and called himself a "sensible writer, painter [...], composer of tender Gammes d'Amour". In 1884, the newspaper L'Art moderne publishes 'Trois semaines à l'Académie' with the subtitle of 'Monologue à tiroirs' (a theatre piece with intrigues). It is the first text that Ensor published, but the publication is not signed. Later, however, he used the anagram Senor from time to time. From 1896, he published in Le coq rouge and in La ligue artistique; libre tribune d'art et de littérature (newspapers that were published in Brussels) news reports about the worldly life in Ostend, art criticism pieces (Au musée moderne), satirical pieces on the laureate of the Prix de Rome (Jean Delville), about the brothers Joseph, Arthur and Alfred Stevens, the death of the antiquated Flemish artistic tradition, or satirical reviews of exhibitions. In addition, in the Ostend daily and weekly papers he published similar satirical art criticism accounts.

A considerable portion of Ensor's writings consists of addresses to the introduction of important manifestations. For example, he wrote orations for the organisation of large exhibitions of his work in the Brussels Galérie Giroux in 1919, or in 1921 for the Kunst van Heden/l'Art Contemporain in Antwerp, for a banquet in honour of the La Flandre Littéraire in 1923, for the retrospective exhibitions in the Palace of Fine Arts/Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels in 1929 and in the Jeu de Paume in Paris in 1932, for the installment of his portrait bust in Ostend in 1930, for the performance of the ballet La Gamme d'Amour in Liège in 1927 and in Ostend in 1932, for the dealings of the decorations of the French Légion d'Honneur in 1933, for the celebration of his honorary title 'Prince of Painters' at the Bal des Artistes in 1934 and for the festivities of his 75th birthday in Ostend. The speeches apparently were popular as Ensor was requested often. Subsequently, he wrote laudatory speeches for Auguste Oleffe (1920), Grégoire Le Roy (1920) Isidoor De Rudder (1920), Jules Destrée (1921), Claude Bernières (1923), Pieter Bruegel (1924), Henri Cassiers (1925), Amedée Lynen (1924), Karel Van de Woestijne (1925), Carol Deutsch (1929) and for other exhibitions that Blance Hertoghe organised in the 1930's in the Ostend Galerie Studio.

The first publication of a large selection of Ensor's writings was published in 1921 by Sélection. Les écrits de James Ensor, avec 36 réproductions d'après les dessins originaux du peintre bundled together 24 texts. La Flandre Littéraire. Revue mensuelle d'art et de littérature that appeared from 1922 to 1927 published loose texts by Ensor every now and then, and in 1926 ensured for a new collection of recent texts. The Antwerp exhibition association, Kunst van Heden/L'Art contemporain, published then in 1934 a third collection with recent writings. The plan of André De Ridder, art critic and economist, to make an edition of all writings, was carried out just after WWII. The 63 texts that were published in 1921, 1926 and 1934 were brought together anew in Les écrits de James Ensor, published in Brussels by Editions Lumière in 1944. After Ensor's death, one Dutch edition and more French editions were published. None of these is exhaustive. Dozens of manuscripts are preserved in public and private collections.

In Le Mal du Pays, Autobiographie de la Belgique (Paris 2003), the French-language writer Patrick Rogiers called Ensor, "the greatest writer, creator and illustrious one of the Belgian language of the 20th Century". Ensor loved humorous litanies, an archaic vocabulary and neologisms. At times, his language use duly put to the test the patience of non-francophone readers. Ensor also spoke Dutch, the language of his mother and her family. He did not have a strong command of Dutch, but did still produce a few texts.

(Text: Herwig Todts)